The 4th Wisconsin Infantry in Howard County

Service at Relay House, 7/29/1861-11/4/1861.

Primary Sources

Archival and Secondary Sources

The 4th Wisconsin Infantry regiment, comprising just over 1,000 men, mustered into service on July 2, 1861 at Camp Utley in Racine, Wisconsin. The unit was comprised of ten companies recruited from the counties of Calumet, Columbia, Fond du Lac, Jefferson, Monroe, Oconto, Sheboygan, St. Croix, and Walworth. These companies had colorful names such as the “Oconto River Drivers”, the “Geneva Independents”, and the “Whitewater Light Infantry.”

From Racine they journeyed by train via Chicago, Toledo, Cleveland, Buffalo, Corning, NY, Elmira, NY, Williamsport, PA, and Harrisburg, PA, finally arriving in Baltimore on July 23, 1861. At each stop of the journey they were greeted by “refreshments and pretty girls” providing “tempting viands”. In Buffalo they were escorted through the city by a brass band. When they reached Harrisburg they received word that their orders had been changed and their new destination was to be Baltimore instead of Washington, D. C. Continued worrying over the loyalties of the border state, and a desire to garrison the city and guard nearby strategic locations necessitated the change of orders.

Upon reaching Baltimore on July 23, they marched through the city with muskets loaded, but unlike the 6th Massachusetts just a few months earlier, encountered no opposition in that divided city. They camped at Mount Clare, on the outskirts of Baltimore. Mount Clare was an ironic camping location for the 4th, as it was built by the same man who laid the first stone in the building of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1828. The 4th was destined to spend the next three months guarding this same railroad.

“HIGH PRIVATE”, writing in the Sheboygan Journal of August 7th, penned the first of a series of letters back home. He described the march through Baltimore, the local landscape and weather, and stated:

“We now have to be very careful of what we eat and drink, for the traitors here, as everywhere, hesitate not to poison the soldiers. Several of the men connected with other regiments here, died yesterday from the effects of poisoned food. I stepped into a Coffee House this morning and called for a lemonade with a “fly” in it but I made Mr. Man taste of it before myself.”

Almost immediately the 4th was split up into several contingents to guard military and other strategic locations. Two companies were sent to Pikesville to guard the arsenal there, while three more were sent to the Relay House, some 8 miles out of town and the junction of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the Baltimore and Washington Branch Railroad. The men were to become intimately familiar with the Relay House and its environs.

Charlie Allyn, a member of the Regimental Band, wrote to the Hudson North Star on July 28, from Camp Dix in Baltimore, describing the warm weather and sleeping on the ground with rubber blankets “to keep the dampness off”. He went on to say “We have plenty to eat, and that which is good. We have bean or rice soup once a day, coffee twice a day, and fresh beef occasionally.”

The next day the unit moved to the newly named Camp Randall, near the Relay House (present day Elkridge, MD.) Another correspondent back home, under the nom-de-plume “CAMP” described arriving after dark in a miserable rain storm on the evening of July 29th. The next morning he set out to examine the locality. He wandered about the small town, identified the Relay House Tavern, the Thomas Viaduct, spoke to a member of the “peculiar institution”, and breakfasted upon the top of a nearby hill.

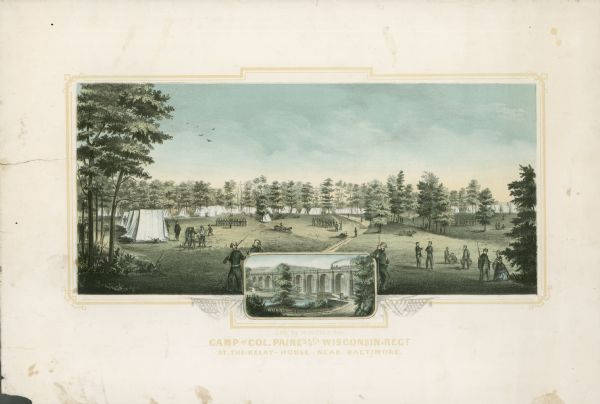

“Camp of Colonel Paine's 4th Wisconsin Regiment at the Relay House near Baltimore”“. Colored lithograph.

Wisconsin Historical Society

HIGH PRIVATE, again writing to the Sheboygan Journal described the location:

“Our location is a most beautiful one, in a grove, overlooking the country for miles around. We take the place of the Massachusetts 6th…COL. PAINE has occupied a beautiful gothic cottage, lately occupied by Lt. MURRY, secessionist, as his headquarters. The hospital is also in the building.”

The duties of the 4th Wisconsin involved breaking the unit up into small contingents of 8-10 men and stationing them at all strategic locations along the railroad; intersections, cuts, switches, and bridges were all guarded. Men stood guard all night in pairs, or roamed through the countryside to prevent saboteurs. Guard duty was hazardous and often harrowing. De Have Norton, in a letter to his father described scouting duty:

“I will explain the method of scouting with a picket…We…marched three miles and then scattered all over the country. I then took my post with L. Carlton - two are allowed to go together. We went all over the space of six or eight miles, when we sat down to rest for a little time, it being about 1 o'clock at night. Suddenly the sharp crack of a musket rang out on the still night air, and a bullet went whizzing over our heads; at the same time several guns went off. I sprang to my feet, mighty quick, you may guess, and went skulking round (I did not know that I had so much courage before) but could not see anything. The camp were all under arms in about five minutes, but no further firing took place.”

Norton's fears were not unfounded, pickets were regularly shot at, tracks torn up, and attempts at poisoning the Union soldiers were all reported in the immediate area.

Leon C. Bartlett, a member of Company C, humorously described his company's first attempt to camp at the Relay House, in a letter to the Evergreen City Times:

“This is the most uneven country I ever came across. We searched the country five miles around to find a level spot large enough to pitch the tents for one company but in vain. We had to encamp on a side hill, and about every other night we have a regular splashing, dashing, crushing rain storm, and we are drifted away like floodwood to the foot of the hill to dig ourselves out and find out who we are.”

In another letter in the same paper “Co. C” echoed the rhetoric of many soldiers, proclaiming “We have come here to fight out a long and bloody war…Many of us will never see Wisconsin again; all of us will be very much changed and almost strangers at home when we return.”

On August 4th, a member of Company D was shot in the hand while on picket duty. The “supposed assassin” was captured and taken to Fort McHenry. A week later John Needham, of Company D, was killed by a train. He had pitched his tent within a few feet of the tracks, and apparently was awoken in the night by an oncoming locomotive, panicked, and stepped in front of the train. Another soldier, James Smith, of Company I, died in the hospital of neuralgia. Sickness was beginning to affect the camp.

Daily routine at the camp involved drilling for several hours, for those not on picket or guard duty. Two members of the Massachusetts Eighth Regiment drilled the men from 6 a.m. to noon each day. Tedious duty at a time when the weather was reaching 103 degrees! In their spare time men smoked, played poker, picked blackberries, wrote letters home, and improved their camping situation. HIGH PRIVATE wrote “We are now 'enjoying all the comforts of a home,' having just had board floors placed in our tents, together with tables and stools made after the most approved patterns. In fact we have so many different varieties of furniture that no two pieces are alike…The boys in our tent chain up our table every night for fear it will run off.” Straw was collected to make their beds more comfortable.

Reports of secessionist troops drilling locally kept the men on their toes. Company I found forty rifles and a small cannon hidden in an old house. A few weeks later a company found fifty guns and two cannons hidden under a bridge.

By mid-August sickness had spread in the camp. Sidney L. Smith of Company A reported “There has been a great deal of sickness in the regiment…though only one case has proved fatal.” One man in Company F died of typhoid. Another soldier, from Company I, was accidentally shot by a comrade.

Being stationed on the only railroad connecting the nation's capital with the populous and industrial north, the members of the 4th Wisconsin had an opportunity to see “the almost fabulous amounts of war impliments, equippages, &c., which are daily being forwarded…”. HIGH PRIVATE went on to quip “From the number of cannon, gun carriages and horses which pass almost daily, I should judge that Artillery was to play an important part in the campaign hereafter. And the large number of ambulances which are being forwarded on to Washington indicate the somebody is going to be hurt. They do not look at all inviting to your correspondent. Not a bit.”

Military law and discipline extended to civilians. In late August two civilians were brought into camp on charges of stealing peaches. The soldiers of the 4th eagerly turned out to watch as the thieves were marched around with the peaches on their backs, as camp servants followed with broomsticks and “other weapons as they might select.” The thieves were court martialed and marched to the drill grounds, amidst the jeers of the soldiers and servants, and ordered to return the peaches.

At the end of August, Company H, the “Oconto River Drivers” were ordered to guard the railroad between Relay House and Annapolis Junction, a distance of nine miles. Every half a mile along the railroad five to seven men pitched tents. Two sergeants took possession of houses belonging to secessionists as their camping location.

By September the weather had begun to cool off, although the 4th remained at Relay House guarding the railroad. Rumors of impending moves to Washington, D. C. were rife, but it appears local citizens, pleased with the behavior of the Wisconsin boys, petitioned to have the regiment remain at the Relay House. The regiment was paid by a U. S. Paymaster, bringing $40,000 in gold and Treasury notes. Many soldiers sent money home, but most was used quickly by the men at Sutler's shops and in commerce with locals. Fresh oysters were ten cents a peck, peaches were seventy-five cents a bushel. Whiskey was also available.

A rumor that Jefferson Davis had died swept through the camp early in September. “CAMP”, writing in the Manitowoc Herald, believed the rumor and thought “How different would have been the reception of this news one year ago! Then the entire nation would have wept a lost son - have mourned a loss irreparable…Such is the traitor's doom. Thus Arnold died. This has Davis died.”

On September 14th the 4th moved from Camp Randall to Camp Bean (named for their Lieutenant Colonel), on a high hill overlooking the Thomas Viaduct. Entrenchments were begun and a battery of artillery was to be placed on the heights. More deaths occurred, Julius Hubbard of Company D died of typhoid and was buried in the Methodist graveyard. James Hart, of Company K also died of typhoid, while his comrade Jackson Chicks was sick with the same disease.

In late September the unit received new uniforms, as their old ones were too similar to the Confederate uniforms. The uniforms consisted of dark blue coats and pants, long skirts and brass buttons. Men received overcoats, dress coats, a pair of pants and cap, two undershirts, two pair of socks and a pair of shoes, all of good quality. George Lanning of Company H ”…says he can sell clothes enough to nett him as much wages as he ever realized on the Oconto [River].“

In early October the regiment moved yet again, this time to the drill ground they had previously used while at Camp Randall. This new camp was dubbed Camp Boardman, after the Major of the regiment. Soldiers were told that they were now camped upon the same ground as the Marquis de Lafayette camped during the Revolutionary War. Construction of a fort was begun, variously described as being hectagonal or octagonal and holding between 200 and 400 men, as well as five 12 pound cannon.

By mid-October typhoid was raging through the camp. Forty-seven were sick in the hospital and several deaths were reported. Twenty-five men were sick in Company C.

Orders for the regiment to move were received the first week in November. The 10th Maine Infantry was coming to take their place at Relay House, for their own extended stay guarding the railroad. The regiment was paid again, with privates receiving $26. At 10 a.m. on the 4th of September the 4th Wisconsin left the Relay House and proceeded to Baltimore, and thence to an expedition on the Lower Eastern Shore of Maryland. They would return to Baltimore briefly, before beginning an epic journey, even by Civil War standards. The 4th would eventually end up in the swamps of Louisiana. Their original colonel, Halbert Paine, was promoted to Brigadier General; Sidney Bean and Frederick Boardman, the unit's original Lieutenant Colonel and Major respectively, were both killed in action during the war.

Calumet City Volunteers, Chilton

Columbia Volunteers

Geneva Independents

Hudson City Guards

Jefferson County Guards, Jefferson

Monroe County Volunteers, Sparta

Oconto River Drivers

Ripon Rifle Company

Sheboygan County Volunteers

Whitewater Light Infantry